If you haven't experienced the intuition of the infinite, then Schleiermacher believes he can lead you only so far. While he can attempt to outline the journey, in the end you have to experience it for yourself. Past a certain point, anything he has to say about it will become incomprehensible. But through the intersubjectivity of a community that finds at its root just such an intuition, you may find your way.

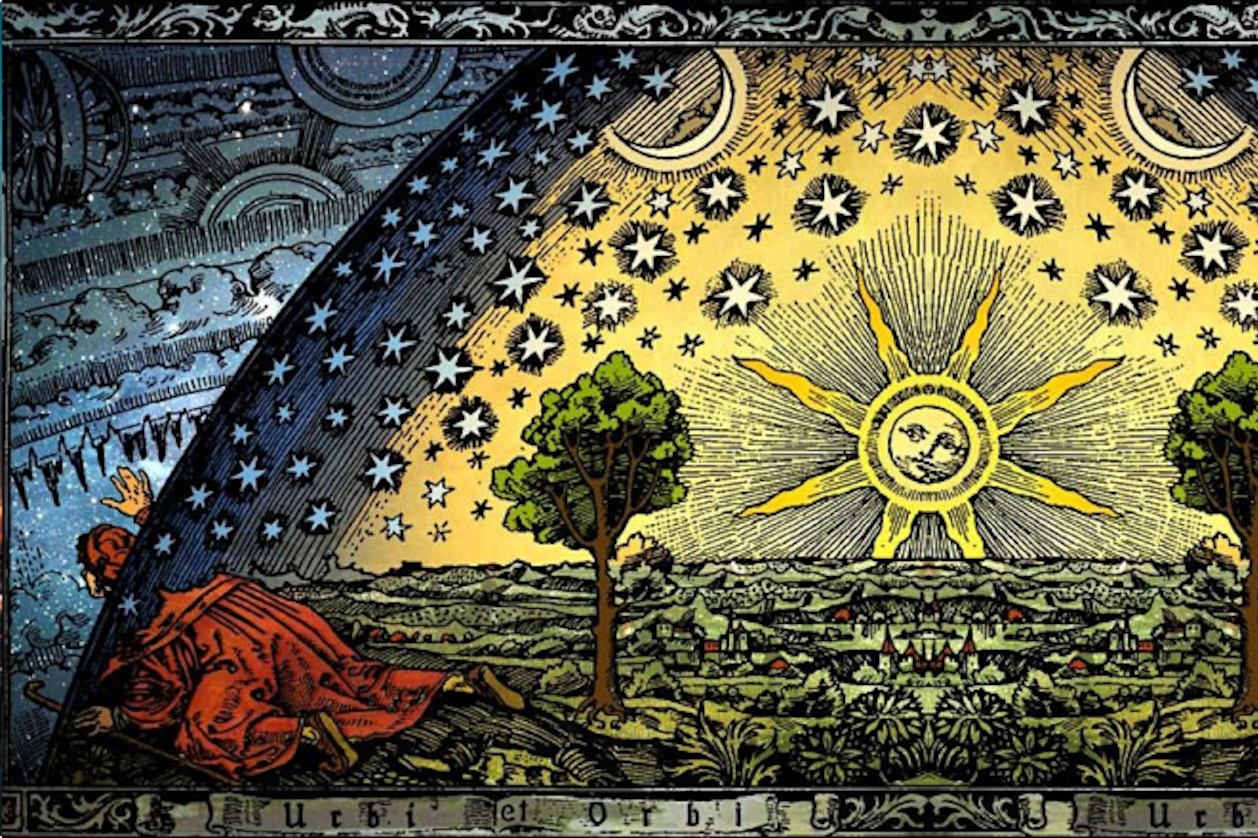

Schleiermacher begins his discussion of the phenomenology of the infinite within the bounds of our corporeal nature. Through observation of the "definite course of the stars" in the heavens and "organic forces" on the earth, we are impressed with the grand scheme of the created order (OR 35).[1]

Schleiermacher begins his discussion of the phenomenology of the infinite within the bounds of our corporeal nature. Through observation of the "definite course of the stars" in the heavens and "organic forces" on the earth, we are impressed with the grand scheme of the created order (OR 35).[1]

But there is more than just the order: in the tradition of German Romanticism Schleiermacher is also drawn to the seeming exceptions to the rules that beckon one to think of an even higher unity that can account for "the anomalies, the superfluous touches of malleable nature," and the arbitrariness and inventiveness within the system (OR 36, also n.23).

Schleiermacher suggests that one must intuit all of these particulars as parts of a larger whole, how a multitude of diverse forms are all "ornately interconnected and intertwined" (OR 36). From intuiting these particulars as part of the whole one comes to an intuition of the universe which "seizes the mind," allowing one to see one unified system created by spirit and permeated by divinity (OR 37).

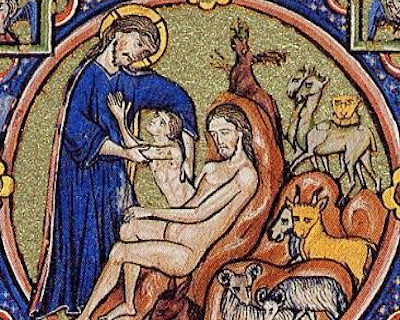

But Schleiermacher claims that in isolation one human cannot attain this understanding. He suggests that for Adam to come into touch with divinity, it was necessary first for him to have a human partner in whom he could discover humanity, and then in humanity the world (OR 37).

Further, for any one of us to come to this understanding we must also find it through humanity, "in love and through love," as a unity. "Each person embraces most ardently the one in whom the world is reflected most clearly and purely; each loves most tenderly the one in whom he believes he finds everything brought together that he himself lacks for the completion of humanity" (OR 38).

Within a single other, one finds a glimpse of the infinite, but Schleiermacher warns of the peril of looking for the ideal humanity in the individual human. Rather, one must consider each individual as a part of the whole of humanity.

Even combinations that one cannot see provide negative revelation of the full spectrum of possibilities within the universe (OR 38-39). Schleiermacher advances then to assigning a task: "Look among all the occurrences in which this heavenly order is reflected to see if there is not one that reveals itself to you as a divine sign. … [S]eek out among all the holy men in whom humanity is immediately revealed one who could be the mediator between your limited way of thinking and the eternal limits of the world; and when you have found him, go through all of humanity and let everything that heretofore appeared to you differently be illuminated by the reflection of this new light" (OR 41).

Schleiermacher suggests that by the lights of this mediator we will be able to empathetically look upon all that previously seemed alien to us in others, finding instead that they are "mere arrested moments of [one's] own life." "[Y]ou yourself are a compendium of humanity; in a certain sense your personality embraces the whole of human nature, and in all its versions this is nothing but your own self that is reproduced, clearly delineated, and immortalized in all its alterations." At this point one has grasped the infinite nature of humanity, no longer requiring a mediator, but now capable of being a mediator to others (OR 41).

But this is only a "resting place on the way to the infinite." Schleiermacher insists that one who has not experienced this particular revelation as mediated through humanity can understand nothing further (OR 44).

Key to Schleiermacher's understanding then is Jesus Christ, alluded to earlier in the speech as "an old rejected concept" (OR 41). It is through Christ, who was fully in touch with the infinite, that the first community of disciples received a mediated intuition of the infinite.

This intuition has ever since been passed down through the church. In the Fifth Speech, Schleiermacher briefly notes that "everything infinite requires higher mediation in order to be connected with the divine" (OR 120).

This intuition has ever since been passed down through the church. In the Fifth Speech, Schleiermacher briefly notes that "everything infinite requires higher mediation in order to be connected with the divine" (OR 120).

Thus he postulates that Jesus, as the Son who knows the Father, reveals (mediates) this intuition to others, both in his life and teaching, but also in the eucharistic symbols.

An intuition of the infinite is mediated to successive generations through the community of those who trace their own understanding back to Jesus.

[1] Citations in this essay from Schleiermacher's Speeches refer to Friedrich Schleiermacher, On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers, Cambridge texts in the history of philosophy (Cambridge [England] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

How, according to Schleiermacher, does one arrive at an intuition of the infinite?